Sunday Inspiration: Unforgettable

I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.

—Maya Angelou

Fantasy Kindreds of Saynim: Humans

I might not have included a post on humans in this survey of the fantasy kindreds you’d find in my work in progress Shadow of the King except for the distinctive role they play in the story world. So let’s go…

HUMAN (Homo sapiens sapiens)

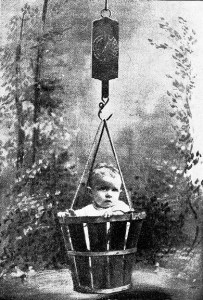

Humans are not native to the realm of Saynim. In fact, they are a distinct minority. Those who live there are either “overbrought,” taken from the mundane world either in infancy or at a later age, or the descendants of those so taken. These humans were taken from their own world for various reasons, both benign and sinister.

Humans are not native to the realm of Saynim. In fact, they are a distinct minority. Those who live there are either “overbrought,” taken from the mundane world either in infancy or at a later age, or the descendants of those so taken. These humans were taken from their own world for various reasons, both benign and sinister.

Benignly, some humans were removed as young children from situations of abuse or neglect. Others found refuge in Saynim after escaping from dire situations such as domestic abuse, abject poverty, or systemic oppression. There is a Cherokee legend about the Nunnehi rescuing the people of certain towns from the Removal by whisking them away to their own magical domain.

Still others were “recruited”—perhaps with selfish motivation—because they possessed certain qualities deemed desirable to a particular otherworldly party. For instance, an elf might fall in love with a human and invite him or her to join this alien world.

At other times, however, folklore describes humans brought into the Otherworld for more sinister reasons. They might be taken as slaves to serve in either the harems or the armies of a powerful fae lord. The Cherokees believed water cannibals would steal children for food. The okwa naholo (“white water people”) of Choctaw mythology would lure swimmers to their underwater domain and, if they stayed long enough, would become okwa naholo themselves. Of course, sometimes humans are taken capriciously, for no discernible reason.

So, what roles do humans play in Saynim society? There are certain stereotypes of humans at play, not least among them the idea that humans are tricky and unpredictable. They think outside the box. More than any other kindred, they seem able to resist the pull of magic to become conformed to particular ways of thinking and acting.

All of this makes humans fascinating to elves and the rest, and they are often objects of a benign and patronizing racism that admires them for these unique qualities while ultimately diminishing their personhood. Think of the way some white folks romanticize (and even fetishize) peoples and cultures that they see as “exotic,” and you won’t be far removed from the way many in Saynim think of humans.

Humans rarely serve as common slaves, though they may be bonded to a lord in a more high-status position of servitude as an adviser, teacher, bodyguard, or in some other capacity where quick, unorthodox thinking is desirable. Some fae lords have maintained elite military units of overbrought children raised to be warriors virtually from birth, comparable to the janissaries of the Ottoman Empire. Whether bond or free, many humans end up in the officer corps of various otherworldly principalities.

Other humans find a niche in careers where their adaptability and unpredictability are assets. They might be merchants and entrepreneurs, inventors, artists, theoreticians, spies, adventures, and treasure-hunters.

Fantasy Kindreds of Saynim: Elves

If you’ve followed this blog for a while, you know that I can be a little obsessive about the fantastical humanoid beings one finds in folklore and popular culture? For one thing, I resist using the word “race” to describe these beings. That term is just too fraught with negative historical connotations in a context where we’re describing persons that look almost human but are regarded by everyone as something profoundly different.

Furthermore, I continue to be intrigued by the analogy between the D&D/Tolkienesque model of multiple fantasy kindreds sharing a world and the actual situation say 300,000 years ago with multiple hominin species sharing planet earth. (A layperson’s definition of a hominin is roughly anything more human than a chimpanzee.)

With my work in progress Shadow of the King nearing completion, I thought I’d share a little of how I personally imagine the kindreds that populate the faerie realm of Saynim. I have tried to keep three goals in mind:

- Be as true to the folkloric source material as possible.

- Work with as many non-European folklore examples as possible.

- Look for connections to what is known or might be postulated about the diversity of hominin species.

I’ll start with elves because, as they’ll gladly tell you, they’re better than everybody else.

ELVES (Homo sapiens pulcher)

Alaric Hall’s PhD dissertation, “The Meanings of Elf and Elves in Medieval England” provides a wealth of data about the elves of Germanic mythology. As originally conceived, they were apparently human-sized creatures, and more often took the side of humans than not. Hall also points out that in Old English, aelf was often used as a gloss when translating classical references to fauns/satyrs and nymphs.

Alaric Hall’s PhD dissertation, “The Meanings of Elf and Elves in Medieval England” provides a wealth of data about the elves of Germanic mythology. As originally conceived, they were apparently human-sized creatures, and more often took the side of humans than not. Hall also points out that in Old English, aelf was often used as a gloss when translating classical references to fauns/satyrs and nymphs.

For my purposes, I take “elf” to mean those fantastical humanoids that look most human, though often possessing unearthly beauty, and that are most likely to have a physical relationship with humans.

In this category I would place not only the nymphs and satyrs of the classical world but also such creatures as the aes sídhe of Ireland and the peris of Iran. In Cherokee mythology, the Nunnehi are elf-like beings who live high in the mountains. They occasionally venture among humans, joining them in their dances and appearing as attractive humans themselves.

In short, I imagine elves as a subspecies of Homo sapiens and therefore our closest cousins among the Saynim folk. Mythology is, in fact, chock full of elf-human hybrid children. “Half-elves” appear in Germanic folklore, for example, with the likes of Hagen of Tronege and Princess Skuld. In Irish folklore, we find Oscar and Plúr na mBan. Outside of Europe, there is also the Arabic legend that says that Bilqis, the Queen of Sheba from the Old Testament, was in fact the daughter of a jinni.

Elves are creatures of grace, subtlety, and powerful magic, especially when it comes to charms and illusions. They tend to conduct themselves with nobility and grace, even if they are not well born. The “faery courts” of European folklore reflect the elvish conception of refinement and sophistication. At the same time, elves are the haughtiest and most easily offended of all Saynim folk—and woe to the one who causes the offense!

In the earliest mythology, elves were generally on the side of good. It may not be that they followed a moral code that humans would recognize, but more often than not, they could be convinced to be on “our” side. In Germanic cultures, offerings were given to the elves to ensure their good favor. All of this changed, however. By the time of Beowulf (c. AD 1000), elves were listed among giants and demons as enemies of humankind. Now, elves are more often seen as a threat: they blight crops, steal babies, and inflict various diseases on humans and livestock. Interpreters usually attribute this shift to the Christianization of northern Europe, and that’s probably not a bad explanation. In Iceland, where the Old Ways are still prevalent, elves don’t have such a bad reputation. And among the Cherokee, the Nunnehi are still considered defenders of the people.

But then elves shift again in the early modern period. Starting around 1600, elves turn into tiny, comical figures: still mischievous, perhaps, but no longer the creatures of nightmare. Our modern conception of elves as Santa’s helpers or as cheerful shoemakers in the Grimm fairy tale come from this period.

In Shadow of the King, I provide an in-story explanation for this second shift from malevolent demons to diminutive mischief-makers. Perhaps in a later volume I’ll do the same for the first shift from a generally pro-human to an anti-human stance.

Sunday Inspiration: I Don’t Want Peace

If peace means keeping my mouth shut in the midst of injustice and evil, I don’t want it. If peace means a willingness to be exploited economically, dominated politically, humiliated and segregated, I don’t want peace.

—Martin Luther King Jr.

Sunday Inspiration: The Wrong Thing

Few people revel in doing the wrong thing. Most of us just convince ourselves it’s not all that wrong.

—Tim Fall

Sunday Inspiration: Mystery

It looks like I’m going to have to let go of what I expected and enter a mystery.

—Eugene Peterson

Sunday Inspiration: Living for Others

Rivers do not drink their own water; trees do not eat their own fruit; the sun does not shine on itself and flowers do not spread their fragrance for themselves. Living for others is a rule of nature. We are all born to help each other. No matter how difficult it is…. Life is good when you are happy; but much better when others are happy because of you.

—Pope Francis

Ancestry and Culture by Eugene Marshall

Eugene Marshall is a game designer, writer, and editor as well as an associate professor of philosophy. His D&D supplement Ancestry and Culture weds these two interests by exploring how the concept of “race” has been handled in Dungeons & Dragons in the past, and how the game and gamers could handle it better in the future. Marshall’s first 30 pages outlines (1) the problems associated with the language and conceptualization of “race” in modern thought and (2) a simple homebrew method to address these problems. The next 40 pages provide sample adventures featuring these innovations. I’m not going to review these adventures; my interest is solely on how Marshall challenges us to reconsider the concept of “race” in a fantasy setting.

Eugene Marshall is a game designer, writer, and editor as well as an associate professor of philosophy. His D&D supplement Ancestry and Culture weds these two interests by exploring how the concept of “race” has been handled in Dungeons & Dragons in the past, and how the game and gamers could handle it better in the future. Marshall’s first 30 pages outlines (1) the problems associated with the language and conceptualization of “race” in modern thought and (2) a simple homebrew method to address these problems. The next 40 pages provide sample adventures featuring these innovations. I’m not going to review these adventures; my interest is solely on how Marshall challenges us to reconsider the concept of “race” in a fantasy setting.

“Race”

Marshall’s three-page introduction lays out his case for doing away with “race” in D&D. It basically boils down to the fact that this term, as it has been used since the Enlightenment, has more often than not been used to denigrate and oppress others. It is, as many have noted, a social construct, not anything based on actual science. For this reason, I have long preferred to call these population groups “kindreds” and jettison the term “race” completely.

Why should this matter in a fantasy setting when we’re not talking, for example, about Europeans and Asians but about dwarves and elves? Marshall points out that, even though we’re imagining fictitious beings, we tend to imagine them with our cultural blinders on.

In short, monstrous kindreds such as orcs

…are often not so subtly veiled stand-ins for age-old, racist stereotypes…. It’s hard to ignore the fact that, when he first created miniatures for the fantasy races, Gary Gygax chose Turk minis to depict orcs and repainted Native American figures for trolls and ogres. Although orcs and goblins are fantasy races in a fantasy world, they are created and depicted by real people in our world, and the systems of fantasy racism and real-world racism are unavoidably linked. (p. 5)

Even “non-monstrous” kindreds are subject to this kind of othering behavior. That’s why so many dwarves these days are inveterate drinkers who speak with a Scottish accent and love a good fight. In the end, a stereotype is a stereotype, and since all of us playing the game are (presumably) human, we have little choice but to draw on the stereotypes we have learned about other groups of humans. The problem is that we often don’t realize that is what we’re doing.

Character Creation

You’d think after all this that Marshall would advocate only ever playing humans—and humans of a culturally or ethnically “neutral” heritage, at that. In fact, he proposes a tweak to the basic rules of D&D 5e that is so elegant as to be nearly imperceptible while at the same time opening up vast new horizons for character customization.

Marshall proposes that all of the features of any given fantastical kindred can be divided neatly into ancestral traits and cultural traits.

Ancestral traits have to do with biology. They are things like average height, lifespan, and various unique advantages such as darkvision, dwarfish resistance to poison, elfish resistance to charms, etc.

Cultural traits have to do with how one was raised: languages, proficiencies, tendencies toward a particular alignment, and ability score increases (more on that in a bit).

So if you’re playing a gnome, you get all the features and abilities of any D&D gnome played straight from the rule books. I expect for the vast majority of players, that’s where it ends. Ancestry and Culture gives permission to go further but doesn’t require it.

But what if you want to play a gnome that was raised in a community of dwarves? That’s now very easy to do: you get the ancestral traits of a gnome (your species hasn’t changed, after all), but you get the cultural traits of a dwarf.

Now let’s take it a step further and say instead that you want to play a gnome-dwarf hybrid. Suddenly, that kind of character build is ridiculously easy. For the ancestral traits, you split the difference in terms of average height, average lifespan, etc. and you pick one unique ancestral trait from each of your two ancestries. (You get darkvision for free if either of your ancestries offers it.) Then you just decide whether you were raised among gnomes or among dwarves and take the appropriate suite of cultural traits. Or, maybe you want to be a gnome-dwarf hybrid orphan who’s been raised by humans. Then just take the human cultural traits instead. Done and done.

Furthermore, you’re allowed to stipulate that your character was brought up in a multicultural community and choose “Diverse Cultural Traits” instead of the traits tied to any particular race.

Marshall only deals with the fantastical kindreds available under the Open Gaming License, but he offers an appendix with steps for applying the same principles to any kindred you might find in any other D&D game book.

Concerns

I played more than my fair share of D&D and Traveller way back when, but I was mainly interested in Ancestry and Culture for what it might teach me as a fantasy author: how can I do a better job of handling elves, dwarves, etc. in ways that don’t fall into the old racist pitfalls that have plagued fantasy fiction as well as fantasy gaming. And I’ve got to say, Marshall provides some well-reasoned guidance.

There are three areas where, to my taste, his system as written is somewhat unsatisfying. With two of them, Marshall anticipates my quibble and explicitly addresses it. With the third, I see where he is coming from and he does, in fact, concede that there might be another valid solution, though perhaps an unnecessarily complicated one.

Genetic Free-for-all. Marshall sets up a system where any conceivable hybrid character can exist. If you want a character whose father was a human-dwarf hybrid and whose mother was an elf-dragonborn hybrid, you can do it! But to paraphrase Dr. Ian Malcolm from Jurassic Park, we can be so preoccupied with whether or not we could, we don’t stop to think if we should.

For me (and I acknowledge that this is a personal preference), it’s more interesting to inject a little bit of science here. For example, modern human-Neanderthal hybrids were viable when the mother was human but not when the mother was Neanderthal—at least, there is no evidence of Neanderthal mitochondrial DNA in the modern human genome today. These kinds of considerations add a little extra flavor that I find fascinating.

Marshall concedes that issues of realism might factor into how much hybridization is acceptable in a given campaign world. His response: If this bothers you as a DM, don’t allow it.

Monolithic Cultures. Another concern has to do with painting all elves, halflings, or what have you with the same broad cultural brush. In a rich, realistic world, elves don’t all speak the same language, follow the same religion, uphold the same cultural values, etc. any more than all humans do. Doesn’t it make sense that the Elves of the Northern Mountains would have a different culture than the Elves of the Mystic Forest?

To address this, Marshall provides a one-page appendix on how to describe a “custom” culture that can plug into his system quite easily. This is the kind of thing that I’d love to see expanded upon, but that would obviously go far beyond the goals of this supplement. Every campaign world is different, and such a project would quickly grow to encyclopedic lengths.

Ability Score Increases. Here is the one place where, in my opinion, Marshall’s system is a bit too simple: He attributes all ability score increases to cultural rather than ancestral factors. I understand why he did that, and I don’t fault him for it. I’ll let him express himself in his own words:

Some readers may wonder why ability score increases appear in culture rather than ancestry. This choice allows us to move away from the problematic notion certain ethnic groups have higher strength or intelligence, as those notions are often at the heart of racist attitudes in the real world. And rather than removing ability score increases entirely, or dividing them up in some more complex way such as a point buy system, these rules keep them under the umbrella of culture for simplicity and ease of use. (p. 9)

In effect, Marshall is inviting us to see these bonuses as the result of a particular kind of upbringing: one that favors athleticism, physical resilience, studiousness, rhetorical skill, or what have you.

There is nothing unreasonable about this approach, especially if everyone around the table playing an orc or whatever is actually a human being enmeshed in their own experiences with race and racism. We’ve all heard how some populations of humans are “more athletic” than others but “less intelligent,” and we all know how those stereotypes have been exploited by other humans in positions of power.

Still, suppose someone uses Marshall’s guidelines to include goliaths in their campaign world. In D&D lore, a goliath is a human-giant hybrid. They stand between seven and eight feet tall and can weigh over 300 pounds. Shouldn’t such a character possess considerable physical strength based on their genetics, quite apart from what culture they were raised in?

In his sidebar quoted above, Marshall himself concedes that it would be possible to divide up the ability score increases in some more complex way. Presumably, he can envision ways of doing so that would not insensitively parrot real-world racial stereotypes.

I expect there are ways to handle these cases that don’t throw a wrench into Marshall’s system overall. Perhaps, for example, it could be as easy as giving goliath characters an ancestral trait called “Gigantic Ancestry,” corresponding to the “Fey Ancestry” of elves and the “Draconic Ancestry” of dragonborns. Let this trait provide some kind of boost to brute strength, hardiness, or whatever, essentially splitting the ability score modifiers between ancestry and culture. Maybe something similar could be done with a number of kindreds, if not all of them. Such a system would have to be rather complex, however. And simplicity of design is nothing to be sneezed at in a tabletop RPG.

Bottom Line

I found Ancestry and Culture to be a stimulating read. Admittedly, Marshall was addressing concerns that I have expressed before. Rather than simply bemoaning how “race” has been mishandled in the past, he offers a clear, simple, and (I think) imminently playable alternative. Get this book if you play D&D or any other RPG that deals with characters from a variety of fantastical kindreds; it will give you food for thought. Get this book if you’re a fantasy writer who seeks guidance in avoiding some of the racist pitfalls that can come with that genre—but do not need to.

Sunday Inspiration: The Ultimate Measure

The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.

—Martin Luther King Jr.

Fantasy “Races,” Again

I’ve previously commented on my aversion to the term “race” in reference to fantastical beings like elves, dwarves, and the like. My preferred term is “kind” or “kindred,” but that’s neither here nor there.

Now I’ve learned via Charlie Hall at Polygon that Eugene Marshall has worked out a way to convert some of my concerns into Dungeons and Dragons terms. Marshall is not only an author and game designer, he’s also a professor of philosophy who knows of which he speaks when he points out the moral and philosophical bankruptcy of the whole construct of “race” as the term has been used in the past few hundred years.

Marshall is the author of Ancestry and Culture: An Alternative to Race in 5e. He replaces the longstanding template of “choosing a race” in D&D with a choice of both a culture and an ancestry. Your culture might give you a stat bonus in intelligence or constitution, but your biological ancestry determines things like height, life span, and special abilities like dark vision. His system allows for a multiplicity of diverse ancestries, and even provides perks for characters with a diverse cultural heritage.

As Hall writes,

With Ancestry & Culture, diversity is no longer a bludgeon that Dungeon Masters beat their players over the head with. Marshall’s system is permissive, rather than restrictive. Diversity ascends from being merely a tool to cast orcs and drow as the “other.” Instead, it becomes a boon from which players can draw their own strength.

Hear, hear!

For ten bucks, I expect I’ll be picking this up at Drive-Thru RPG. The excerpt from the introduction that Hall provides is nearly enough to sell me on the product.

For what it’s worth, Marshall’s approach is similar, but not identical, to what I’ve been doing in my fantasy novels. Characters have a “kindred,” a biological ancestry (elf or dwarf or whatever); a “chaos,” an elemental affinity that shapes their magical potential (air, water, etc.); and a “culture,” the nuts and bolts of the languages they speak, the customs they observe, the technology they use, and so forth.

Unlike Marshall, I’m imagining a situation somewhat like the prehistoric real-world earth, with various members of genus Homo interacting with one another in various ways. (And the situation here is looking more complicated all the time.) Not all of these populations are interfertile, so not all mixed ancestries are possible, and I’ve tried to put a little bit of science into the implications for those that are (cf. the nature of sapiens-Neanderthal interbreeding in the lower Paleolithic). Still, I expect I will thoroughly enjoy Marshall’s supplement.