Fairies in the Bible?

Speaking of Jewish folk beliefs, a few years back I wrote a piece about fairies in the Bible at my other blog. Some of that material, with some elaboration, found its way over here in my post on “Shedim: Eldritch Beings from Jewish Folklore.” Here is the full, original post from July of 2013, only slightly edited:

Joel Hoffman has written a blog post about unicorns and other mythological creatures in the Bible—or at least in the King James Version. As he usually does, Dr. Hoffman raises an intriguing question about how the original Hebrew words the KJV rendered as “dragon,” “unicorn,” and so forth should be handled. Did the original writers intend their readers to understand these as real-world creatures (e.g., as serpents, rhinoceroses, etc.) or did they mean to depict creatures of fantasy? He writes,

More generally, I think the real translation question with all of these creatures is whether they were intended to be mythic or — for want of a better word — real.

Even if they were intended to be real, “dragon” and “unicorn” may have been right once. It seems that people thought that both existed. (As late as the 17th century, scholars in Europe argued that griffins were real, and the only reason we didn’t see them was that, quite naturally, these magnificent creatures tended to stay away from people who would steal their gold). But now those translations wrongly take the real and turn them into fantasy.

On the other hand, if they were not meant to be real, then attempts to identify the exact species may be misguided, and maybe we should stick with “dragon” and “unicorn” and so forth.

Hoffman deals mainly with “unicorns” (re’em) and “dragons” (tannin), although he makes passing reference to a possible merperson in the character of Dagon, the god of the Philistines.

Along these same lines, I would suggest that there are a handful of possible reference to fairies in the Bible—at least if the rabbis of the medieval period were interpreting these passages rightly.

Two Hebrew words are of interest: shedim and se’irim, both translated daimonia (“demons”) in the Septuagint. Shedim only appear twice in the Hebrew Bible, both times in the plural (although the singular form would be shed or sheid). Psalm 106:37 says, “They sacrificed their own sons and daughters to demons!” (CEB). In a similar context, Deuteronomy 32:17 says,

They sacrificed to demons, not to God,

to deities of which

they had no knowledge—

new gods only recently on the scene,

ones about which your ancestors

had never heard.

Shedim are therefore obviously bad news in the Bible. Oddly enough, the term seems to be related to the Akkadian shedu, a benevolent or protective spirit, perhaps something we might think of as a guardian angel. Then again, people around the world have made offerings to various local protective spirits to secure their goodwill. The biblical writers were obviously interested in discouraging such a practice. Thus, in the Bible, they are depicted not as helpful minor spirits but as false gods to be avoided.

The next word is se’irim (singular se’ir), meaning “hairy beings” or “shaggy beings.” In the KJV, the word is translated “satyrs.” There are a few more references to se’irim than there are to shedim. According to Leviticus 17:7, “The Israelites must no longer sacrifice their communal sacrifices to the goat demons that they follow so faithlessly. This will be a permanent rule for them throughout their future generations.” The LXX renders se’irim as mataiois, “to empty or vain things.”

Se’irim dwell in the desolate wilderness and are apparently fond of dancing. According to Isaiah 13:21,

Wildcats will rest there;

houses will be filled with owls.

Ostriches will live there,

and goat demons (LXX, daimonia) will dance there.

And again in Isaiah 34:14:

Wildcats will meet hyenas,

the goat demon will call to his friends,

and there Lilith will lurk

and find her resting place.

I saw you wondering about Lilith in that verse. We’ll come back to her in a minute. It should be noted, that the Septuagint translation removes Lilith from the picture but possibly gives us a completely new mythological creature. My fairly wooden translation of the Greek is as follows:

Demons will meet onocentaurs

and they will shout one to the other,

There onocentaurs will rest

for they found a resting place for themselves.

If you’re not up to speed on medieval bestiaries, let me quickly explain that an onocentaur is part man, part ass. (And please refrain from any comments about half-ass blog posts. Thank you.)

According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, the se’irim are “are satyr-like demons, described as dancing in the wilderness…identical with the jinn of the Arabian woods and deserts.” Azazel, the goat-like wilderness demon (Lev 16:10ff) and Lilith (whom we already encountered in Isa 34:14) are said to be of the same class of beings. Further, it should be noted that some see in Lilith a prototype for later vampire legends. The Jewish Encyclopedia also raises the possibility that “the roes and hinds of the field” (gazelles and wild deer in the CEB) in Song of Songs 2:7 and 3:5 are “faunlike spirits similar to the se’irim, though of a harmless nature.”

How does all this apply to fairies? Thomas Keightley argued in The Fairy Mythology (1870) that the prototypes of European fairy legends were to be found not only in the nymphs and satyrs of Greco-Roman mythology but also in Near Eastern stories of jinnis and peris (or jinn and parian, to use the correct Arabic and Persian plurals). He even argued that our English word “fairy” derives ultimately from Persian pari (or peri). This linguistic argument may or may not hold, but anyone who looks at Persian peri-stories will find many parallels to what was believed about fairies in rural Europe until fairly recent times.

If Keightley is correct, then the European conception of fairies owes a good deal to the Mediterranean and Near Eastern world(s) in which the Bible was written. It therefore would not be unusual to find references to the such creatures in biblical and other early Semitic materials.

After tracing the fairy mythology throughout northern Europe, Keightley makes quick reference to Jewish legends about similar creatures found in the rabbinic corpus. These beings are in fact called shedim and seirim (although Keightley transliterates them shedeem and shehireem). Another term, maziqin (or mazikeen in Keightley’s transliteration), is Aramaic and applies specifically to a malevolent spirit. According to rabbinic tradition, all these beings are in fact directly analogous to the jinn of Arabic folklore. Keightley writes,

It has long been an established article of belief among the Jews that there is a species of beings which they call Shedeem, Shehireem, or Mazikeen. These beings exactly correspond to the Arabian Jinn; and the Jews hold that it is by means of them that all acts of magic and enchantment are performed.

The Talmud says that the Shedeem were the offspring of Adam. After he had eaten of the Tree of life, Adam was excommunicated for one hundred and thirty years. “In all those years,” saith Rabbi Jeremiah Ben E’liezar, “during which Adam was under excommunication, he begat spirits, demons, and spectres of the night, as it is written, ‘Adam lived one hundred and thirty years, and begat children in his likeness and in his image,’ which teaches, that till that time he bad not begotten them in his own likeness.” In Berasbith Rabba, R. Simon says, “During all the one hundred and thirty years that Adam was separate from Eve, male spirits lay with her, and she bare by them, and female spirits lay with Adam, and bare by him.”

These Shedeem or Mazikeen are held to resemble the angels in three things. They can see and not be seen; they have wings and can fly; they know the future. In three respects they resemble mankind: they eat and drink; they marry and have children; they are subject to death. It may be added, they have the power of assuming any form they please; and so the agreement between them and the Jinn of the Arabs is complete.

Keightley shares three Jewish legends about the shedim: “The Broken Oaths,” “The Moohel,” and “The Mazik-Ass.”

As with dragons and unicorns, there are probably some who will pounce on “rational” or “scientific” explanations for fairies. Some do, in fact, attribute European fairy-lore to dim memories of diminutive tribes driven underground—and ultimately to extinction—by later invaders with the advantage of iron weapons (in both Europe and the Middle East, iron is a potent weapon against the Fair Folk).

In my experience, however, I think most interpreters would see shedim and se’irim as terms intended to describe supernatural or otherworldly beings and not merely misidentified pygmies or “wild men”—whether or not they judge such creatures to be “real.”

Magic in Early Judaism

This is a bit afield of what I usually post on this blog, but some of you might be interested in a new book about magic in early Judaism. The book is called Jewish Magic before the Rise of Kabbalah. Blogger Alan Brill reviews the book and interacts with the author in a brief online interview.

Harari argues that the practice of magic was very much a part of early Judaism (and Christianity), even though we’re predisposed not to see it. (What I do is “ritual”; what the people I don’t like do is “magic.”) Here’s one small snippet:

Magic is may be considered as pre-scientific technology, a scheme of technical practices founded on the belief in the way reality is run. Given the traditional premises concerning what forces that reality, magic behavior was rational.

Jewish magic is founded on a belief in human aptitude to affect the world by means of rituals, at the heart of which is execution of oral or written formulas. It is not different from Jewish normative religious view, which ascribes actual power to sacrifice, prayer, ritual, and the observance of law. Magic also does not differ from the normative views regarding God’s omnipotence or the involvement of angels and demons in mundane reality. It has elaborated as a system parallel to, and combined with the normative-religious one, a system that seeks to change reality for the benefit of the individual, commonly in order to remove a concrete pain or distress or to fulfill a certain wish or desire.

Books of magic recipes from antiquity as well as from later periods show that magic was pragmatically required in every aspect of life. Magic fantasy of the kind of One Thousand and One Nights or Harry Potter is missing almost all together from recipe books, which usually offers assistance in achieving targets that may be achieved also without magic. According to these Jewish books, magic power can be implemented personally or by an expert. Expert magicians offered their help in choosing and performing the right ritual and in preparing adjuration artifacts and other performative objects, such as amulets of roots and minerals.

Brill’s review mentions connections between early Jewish magic and Greco-Roman magical practices, something I’d certainly be interested in checking out.

Yuval Harari: Early Jewish Magic

Alan Brill reviews Yuval Harari’s recent book Jewish Magic before the Rise of Kabbalah and interacts with the author in a brief online interview. He argues that the practice of magic was very much a part of early Judaism (and Christianity), even though we’re predisposed not to see it. (What I do is “ritual”; what the people I don’t like do is “magic.”) Here’s one small snippet:

Magic is may be considered as pre-scientific technology, a scheme of technical practices founded on the belief in the way reality is run. Given the traditional premises concerning what forces that reality, magic behavior was rational.

Jewish magic is founded on a belief in human aptitude to affect the world by means of rituals, at the heart of which is execution of oral or written formulas. It is not different from Jewish normative religious view, which ascribes actual power to sacrifice, prayer, ritual, and the observance of law. Magic also does not differ from the normative views regarding God’s omnipotence or the involvement of angels and demons in mundane reality. It has elaborated as a system parallel to, and combined with the normative-religious one, a system that seeks to change reality for the benefit of the individual, commonly in order to remove a concrete pain or distress or to fulfill a certain wish or desire.

Books of magic recipes from antiquity as well as from later periods show that magic was pragmatically required in every aspect of life. Magic fantasy of the kind of One Thousand and One Nights or Harry Potter is missing almost all together from recipe books, which usually offers assistance in achieving targets that may be achieved also without magic. According to these Jewish books, magic power can be implemented personally or by an expert. Expert magicians offered their help in choosing and performing the right ritual and in preparing adjuration artifacts and other performative objects, such as amulets of roots and minerals.

Djab: Caribbean Spirits for Hire

Djab are a feature of the Vodun religion, but are associated more with practical magic than with spirituality. Their name is derived from French diable, “devil.” In fact, the same word is found in Louisiana Creole. These beings are not necessarily diabolical, though. Rather, they are what might be called “mercenary spirits”: they are independent supernatural contractors that can be hired or bribed to perform magical work. They must be paid for every job and they can be very aggressive about collections, to the point that they can effectively be the equivalent of supernatural loan sharks.

Djab are conceived as a type of lwa or intermediate spirit between the mortal realm and the Creator. At least some djab are the spirits of deceased mortals—or at least present themselves in this way. It is possible that the “spirits of the dead” interpretation may be the result of Christian missionaries imposing their theological bias upon the legend.

Magical practitioners can summon a djab through spells and rituals. Such spells are typically aggressive and less than savory—means of invocation that other spirits will refuse. Furthermore, djab are willing to do malevolent work from which other spirits may shy.

Djab may serve as guardians to a spell-caster if so requested. They prove to be formidable bodyguards willing to search out and destroy enemies. They are also sometimes invoked to serve justice when it is otherwise not found. Some djab are truly scary and unpleasant while others are just exceptionally independent. Each djab tends to manifest somewhat differently.

Particular djab might be affiliated with a person or a family—who may or may not be able to exert control over it. Like a European-style domestic spirit, it passes itself down from one generation to the next and is treated like one of the clan. Other djab, however, are wild, autonomous spirits who play by no rules but their own.

A “djab-djab” (or “jab-jab”) is a traditional costumed figure of Carnival. They are described as:

men in jester costumes, their caps and shoes filled with tinkling bells, cracking long whips in the streets, with which they lashed at each other with full force, proclaiming in this display that they could receive the hardest blow without flinching at its coming, while feeling what, at its landing, must have been burning pain. (Richard and Jeannette Allsopp, Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage [Oxford University Press, 1996] 194)

A female djab might be called a djablès (diablesse), but usually djab serves for both male and female, both singular and plural. (Djablès or “devil woman” usually refers to an evil creature that appears on a lonely road in the form of a pretty young woman, who lures men into the woods. There, she reveals herself to be an old crone with cloven hooves and causes her victim to either go mad or die.)

Sunday Inspiration: Helpers

When I was a boy and would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, “Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.”

—Fred Rogers

A Note about Fantasy “Races”

TL;DR: When differentiating between humans, elves, dwarves, etc., “kind” is preferable to “race.”

In much fantasy literature, we hear of various “races,” meaning elves, dwarves, orcs, and so forth. The more I think about that terminology, the less I like it. A while back I looked at some of the fanciful humans or near-humans one encounters in the ancient and medieval geographies, populations traditionally called “monstrous races.” At that time, I took exception to that term because of the potentially hurtful connotations of both “monstrous” and “race.” In my introductory post, I wrote:

That can also be an awfully loaded term with a dubious past in pseudo-scientific pronouncements that attempted to justify the oppression and enslavement of some groups of human beings by other groups of human beings on the theory that some groups of human beings are naturally superior to others. Originally, a “race” (Latin gens, Greek ethnos) was simply a definable people-group: a tribe or culture, whether sparse or numerous, whether familiar or foreign. Even so, when talking about human beings—or supposed human beings—whose customs are disquieting or who possess animalistic traits, the word “race” can lead us down some paths we might not want to tread.

At that time, I wasn’t concerned with dwarves and the rest but only with cynocephali, monopods, and the like. But as I think of it, my concern with the word “race” still pertains and is perhaps even more pronounced when we use it to describe what makes Legolas different from Gimli.

It seems to me that “species” is an apter description of what these fantasy populations really are. There are clear genetic differences between elves, orcs, trolls, etc. Hybrid or mixed-lineage characters notwithstanding, the ability of at least some of these groups to interbreed seems at least problematic. That means we’re probably in the realm of using the term “race” to speak of what modern science would call a “species.” Dwarves are different from elves at a deep level that goes far beyond physical phenotype or genetic minutiae (e.g., blood types, lactose tolerance or intolerance, susceptibility to certain diseases, etc.). And explicitly, the term “race” is used to set certain groups apart from the “human race.” Once again, that doesn’t sit well with me.

Of course, “species”—a word used in English with a more or less precise scientific definition—doesn’t quite seem at home in a fantasy setting. Fortunately, there is a good English term from the pre-industrial era that can carry the same weight. That word is “kind.” In the King James Version of the Bible (1611), we read,

And God said, Let the earth bring forth the living creature after his kind, cattle, and creeping thing, and beast of the earth after his kind: and it was so. And God made the beast of the earth after his kind, and cattle after their kind, and every thing that creepeth upon the earth after his kind: and God saw that it was good. (Genesis 1:24-25, emphasis added)

“Kind” is thus, roughly speaking, an early English equivalent to what we usually understood by “species” today. I know I’ve read fantasy stories that speak of “Elfkind” or “Dwarfkind.” Perhaps it’s time to retire the idea of “race” as it is used in the genre and speak of “fantasy kinds” (or “fantasy kindreds”) instead.

What do you think?

Sunday Inspiration: Anger

Be not angry that you cannot make others as you wish them to be, since you cannot make yourself as you wish to be.

—Thomas à Kempis

Sunday Inspiration: Children

It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.

—Frederick Douglass

Sunday Inspiration: Fear

Don’t let fear drive you, but it’s okay to bring it along for the ride, so it can help you stay alert.

—Faydra D. Fields

Iroquois Supernatural: Culture, Commodity, Sacred, and Spooky

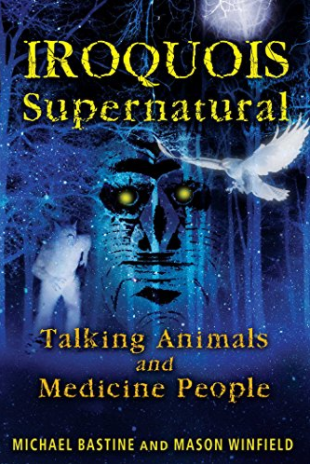

I have great friends. One of them recently found a copy of Iroquois Supernatural: Talking Animals and Medicine People by Michael Bastine and Mason Winfield at a yard sale and was kind enough to pick it up for me as a gift. Bastine is an Algonquin healer and elder. Winfield is a European American who describes himself as a “supernatural historian.”

I have great friends. One of them recently found a copy of Iroquois Supernatural: Talking Animals and Medicine People by Michael Bastine and Mason Winfield at a yard sale and was kind enough to pick it up for me as a gift. Bastine is an Algonquin healer and elder. Winfield is a European American who describes himself as a “supernatural historian.”

This is a really neat, informative book. It is chock-full of fascinating tales, keen historical and cultural insights, and a pervasive sense of respect for the Iroquois culture(s) as a whole. I’m mentioning it not to provide a thorough review. My review can be summed up thusly: If you’re the sort of person who is interested in Native American cultures and particularly Native American mythology and folklore, get this book!

I’m bringing this book up, rather, for the guidance it may provide for writers wanting to handle mythological material from outside their culture with reverence and sensitivity. This is a topic that has recently come up in an article at Fantasy Faction by Brian O’Sullivan with respect to Celtic, and particularly Irish cultural artifacts. (You can also read my observations.)

As when I wrote about the uproar over J. K. Rowling’s handling of Native American mythology, I still believe that there are situations where leaving elements of Native American or African mythology out of a story can be more colonialistic than including them. I’m thinking particularly of stories in the contemporary fantasy genre that are set in North America—which happens to be what I write. Populating North America with unicorns and griffins rather than naked bears and great horned serpents strikes me as a lazy and Euro-centric way to tell a story.

Still, the challenge remains to handle these cultural artifacts with care and not treat them as mere commodities. Here is where Bastine and Winfield’s concerns in writing Iroquois Supernatural intersect with my own admittedly different concerns. First and most basically, writers who want to include these kinds of cultural artifacts need to read lots of books like this one, written from a clearly sympathetic viewpoint.

Second, the authors draw a distinction between what they classify as “the sacred” and “the spooky.” This is a distinction that especially writers from outside a given culture need to keep in mind. In the introduction, they write:

Figuring out what to include in this book has been tricky. Where do you draw the line between miracle and magic? Between religion and spirituality? Between the sacred and the merely spooky? This book doesn’t try to choose. How could anyone? (p. 2)

But then they proceed to explain their preference for the spooky over the sacred:

All religions are at heart supernatural. Throughout history most societies have had both a mainstream supernaturalism and others that are looked upon with more suspicion. The “out” supernaturalism is often that of a less advantaged group within the major society. What the mainstream calls “sacred” is its supernaturalism; terms like “witchcraft” are applied to the others. Someone’s ceiling is another’s floor, and one culture’s God is another’s Devil. To someone from Mars, what could be the objective difference? (p. 2)

This comment reminds me of the privileged place Judeo-Christian supernaturalism has in my own culture. Perhaps it will remind you of something else in your own frame of reference. But the writers go on to admit that within Iroquois society itself there are distinctions between the sacred and the spooky. They conclude,

This book is not about the sacred traditions of the Iroquois. It is a profile of the supernaturalism external to the religious material recognized as truly sacred. This is a book largely about the “out” stuff: witches, curses, supernatural beings, powerful places, and ghosts. (p. 3)

Even so, the authors admit that it isn’t always easy to draw firm lines between sacred and spooky. The fact that one of the authors is a practicing traditional healer within a neighboring Native American community is bound to help in this regard! Later on, we hear Winfield explaining further about their approach to this cultural material:

This is not a book about Iroquois religion or anything else we knew was sacred enough to be sensitive. Not only is that not our purpose, but, as a Mohawk friend said recently to me, “If it’s sacred, you don’t know it.” And coauthor Michael Bastine would not reveal it. (p. 22)

So perhaps we can isolate the following touchstones as the beginning of an approach to including cultural material from marginalized or minority groups within our society:

- Aim for the spooky, not the sacred. Frankly, I’m not interested in writing philosophical or theological treatises on the spirituality of marginalized peoples. (I will admit to a certain interest in reading such studies.) But I love stories about ghosts, monsters, trickster figures, or what have you. As Bastine and Winfield themselves note numerous times, these sorts of things are common to every culture. That suggests to me that, with suitable awareness, writers can fruitfully explore them. If something gets too close to the lived faith commitments of others, however, I tend to want to shy away from it in terms of worldbuilding and storytelling,

- If it is sacred enough to be sensitive, leave it out. I’m well aware that one reaches a point of sensitivity sooner in some cultures than others, and with different topics in some cultures than in others. Still, is there a better place to start?

- Strive to understand as much about the culture as a whole as possible. I don’t want to add a cultural element to a story without a firm grasp of how that element relates to others in its “native” environment. Understanding the ins and outs of a culture and its history is a great inoculation against a grab-bag approach.

Do you think it’s possible for writers to handle other world cultures with sensitivity? When have you seen a writer handle well the artifacts of a culture to which he or she was an outsider?