Understanding Tolkien

Thanks to Keitha Sargent for this engaging summary of some of the things that made J. R. R. Tolkien tick.

To get the most out of Tolkien’s works, it is important to understand a little about the man, his life, passions and views. Several things shaped the imagination from which Middle Earth emerged: his childhood in England, his experiences in the First World War, and his love for ‘Northern’ myth and literature.

Tolkien was born in South Africa to English parents. When he was 3, his father died, and in 1896 the family settled in a small village in central England. In 1966, Tolkien described the place as “a kind of lost paradise” and, for the rest of his life, it remained an ideal. Tolkien had a deep love for England, even suggesting that, thanks to a sort of race-memory, he recognised the Anglo-Saxon language when he first encountered it as a boy.

Closely related to his love for England was his distaste for the modern world. This extended even to literature. For a professor, he was remarkably ignorant of contemporary writers and used to joke “English Literature endedwith Chaucer”, inverting the cliché that Chaucer was ‘father’ of the language. For Tolkien, ‘modern’ was a word with negative connotations; to him it meant industrialism, machines, overcrowding, noise and speed. In 1933, he returned to the village of his childhood and wrote bitterly that the place had been engulfed by trams, roads, and hideous housing estates.

Sunday Inspiration: Growing Old

It is magnificent to grow old, if one keeps young.

—Harry Emerson Fosdick

“Rowling is Better than Shakespeare”

I respectfully disagree with Max Freeman’s titular assertion, but I nevertheless endorse the substance of his post.

Tell me if you’ve ever read these stories before:

– A young male sociopath disapproves of everyone and everything around him, including any of his romantic interests. He changes nothing, learns nothing, and leaves.

– It’s the olden days, and terrible things are happening to good people. Terrible things continue to happen for 200 – 400 pages. Despite all this tragedy, there is little to no story, and no character development. Everyone is either 100% good or 100% bad, from start to finish. In the end, things either get marginally better, or they don’t.

– Wow, what a great dog! Whoops, he’s dead. (Or every character besides the dog is dead.)

– A metaphor commits a metaphor to another metaphor. Everyone is sad.

Do any of these scenarios sound familiar to you? If you went to high school in America, I bet the answer is a big yes. In fact, I bet these few plots encompass around 90% of everything you and I were both forced to read in English class while growing up….

Listen, I’m all for supporting good literature, but it’s not the wordiness or length of these “classics” that put people off. It’s their DULL, unlikeable characters. Wordiness and length didn’t keep kids from reading Harry Potter, did it?

We really need to expand our horizons and incorporate some more fantasy and sci-fi into our kids’ reading. Not only does it expand their imaginations, and introduce memorable characters and journeys, but so many of them are well written too. Here are some humble suggestions.

Sound Exegesis: It Does The Body Good

No purportedly biblical position on any issue is served by sloppy exegesis. Especially when the exegete implies, or downright states, that the possible interpretation he or she proposes is, in fact, the only possible interpretation.

Thus, I commend to you Ian Paul’s “Did Jesus Heal the Centurion’s Gay Lover?” (Spoiler: Maybe, but even if he did, it doesn’t mean what some people want it to mean.)

Sunday Inspiration: Humility

A great person is always willing to be little.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

Sunday Inspiration: Wisdom

Science is organized knowledge. Wisdom is organized life.

—Immanuel Kant

A Scientific Theory of the Origin of Dragons

I’ve just stumbled upon a scholarly article on the origin of dragon-lore in early human cultures: Robert Blust, “The Origin of Dragons,” Anthropos 95 (2000): 519–36.

This is far more highbrow than many of my readers will appreciate, but it’s the sort of thing that stokes my imagination as I think through how I want magic, dragons, and other mythological creatures to “work” in my writing. Here’s an intriguing paragraph from near the beginning:

[T]he idea of the dragon arose through processes of reasoning which do not differ essentially from those underlying modern scientific explanations. Far from being the product of a capricious imagination, the dragon was mentally constructed in many parts of the world as a by-product of 1. meticulously accurate observations of weather phenomena, and 2. an earnest but unsuccessful attempt to grasp the causality of natural events, particularly those relating to rainfall. The dragon thus stands as one of the supremely instructive examples of convergent evolution in the symbolic life of the mind.

By the way, dragons will make their first appearance in the Into the Wonder series with its fourth book, The River of Night, which is currently in the hands of my beta readers. 🙂

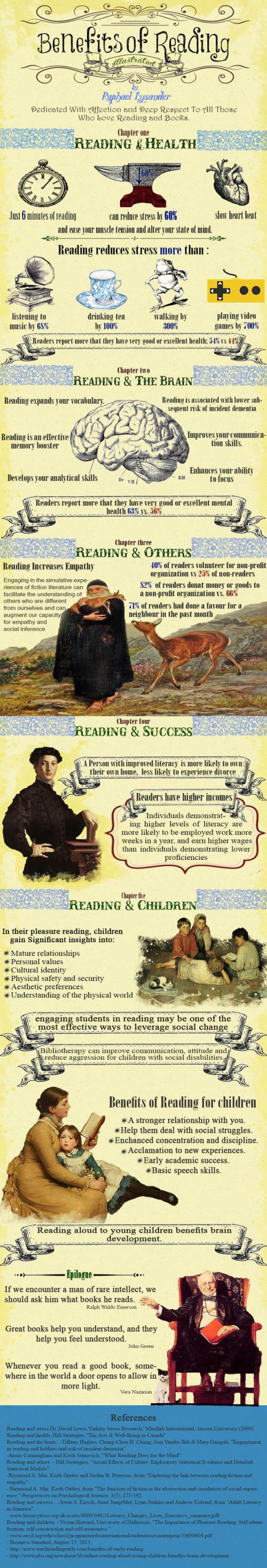

Reading Makes You a Better Person

This infographic by Raphael Lysander explains the many ways in which reading does a body—and a mind, and a soul, and a society—good. (H/T: mental_floss)

On the Importance of Nailing the Landing

I’ve recently read a number of free or bargain-priced Kindle books that should have been right up my alley: They featured heaping spoonfuls of magic, mythological creatures, compelling world-building, mystery, and rip-roaring adventure. But they all had the same problem. They were all the first volume of a multi-book series, and it showed.

To be honest, I like series, and some of my favorite fantasy authors do them exceptionally well (I’m looking at you, Rick Riordan, Benedict Jacka, and Jim Butcher). If the characters are interesting and draw me into their world, I’ll be all over that stuff. But I still want each book of the series to have its own proper conclusion. I want a clear sense of development, that the protagonist has not only left Point A, but that he or she has arrived conclusively at Point B.

I wrote Children of Pride (Into the Wonder, book 1) as a standalone novel. I had an idea of where sequels might go, but I wanted the story to hold together on its own, and my sense is that it does. The Devil’s Due (book 2) has a pretty strong sequel hook. You know more adventures are coming, but the story itself still has a fitting conclusion. The same is true for Oak, Ash, and Thorn (book 3). The River of Night (book 4) is still in production. I think readers will like the conclusion, but the less I say about that right now, the better! 😉

So, I want good stories that stand on their own two feet, but I’m still a big fan of sequel hooks. If you want to throw me hints about a bigger, more dangerous world looming on the horizon, knock yourself out. I can even deal with a well-written cliffhanger. (I prefer not at the end of book 1; your mileage may vary.)

To be bluntly to the point, if I don’t know that you can bring your novel to a fitting conclusion, how can I trust you to do it with a series? Please end your novel and don’t just stop when you’ve reached the desired word-count. Give me a sense of resolution, a sense that the protagonist has achieved the goal he or she set out to achieve, and experienced a little character development along the way.

Do that well, and I’ll gladly read book 2. I promise.

Sunday Inspiration: Extraordinary

We meet no ordinary people in our lives.

—C. S. Lewis