Philip Overby’s March Fantasy Writer Spotlight…

…is actually aimed straight at me!

Philip was kind enough to feature me this month on his Fantasy Free-for-all blog. There’s an interview, an excerpt from Children of Pride, and everything! I’m very grateful to Philip for taking the time to bring greater exposure to some new writers. And I’m already looking forward to whoever is on deck for April!

So what are you waiting for? Get over there and read all about it!

Languages in Fantasy

Leo Elijah Cristea has posted some thoughts and observations about made-up languages in fantasy (and science fiction) over at Fantasy Faction. The bottom line: nobody who doesn’t have a Ph.D. in linguistics is going to do it as well as Tolkien, and even if they could, that’s not what fantasy readers want any more. Characters are everything, and the world-building must serve the characters (and, of course, the plot).

For Children of Pride and its eventual sequels, I’ve roughed out a couple of constructed languages. Esrana, for example, is the ancestral language of many of the fae kindreds of western Europe. It holds a place similar to Latin in the Topside world, especially a few centuries ago when Latin was a “prestige” language spoken by the educated elites. There are some characters (and locations) in Children of Pride whose names are derived from Esrana, just as there are people and places today whose names are derived from Latin or Greek (Julia, Gregory; Indiana, Philadelphia, etc.).

Not yet seen in print is Wechakáhli, the language of certain dwarfish clans. I worked out some of the details of this language just to play around with a language spoken by beings whose vocal apparatus is not entirely the same as that of humans. Other than a handful of vocabulary and a bare-bones grammar, there’s not much to it.

The Hopkinsville Goblin

One of Kentucky’s lesser known claims to fame is a 1955 “goblin” sighting in Hopkinsville. Rob Lammle has the story at Mental Floss.

February 2014 Biblical Studies Carnival

I’m back from my church’s family retreat just in time to alert readers to the most recent Biblical Studies Carnival, hosted this month at Mosissimus Mose.

You might also want to check out the seventh installment of Abram K-J’s Septuagint Studies Soirée.

And finally, Brian Small has once again provided a rundown of interesting recent posts on the most fascinating book in the New Testament.

Sunday Inspiration: Success

Success is walking from failure to failure with no loss of enthusiasm.

—Winston Churchill

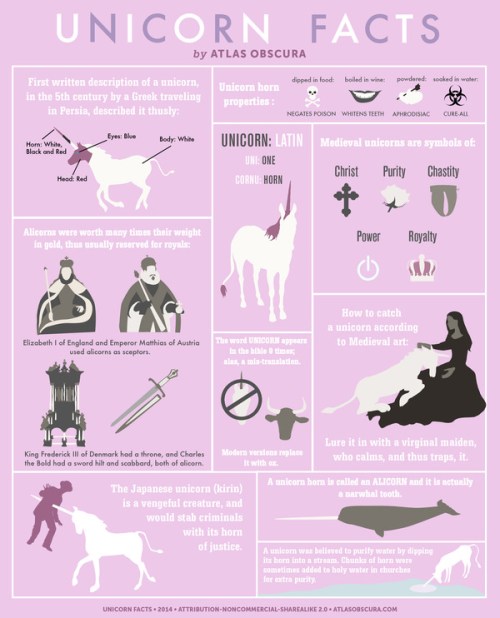

Unicorn Infographic

Michelle Enemark at Atlas Obscura has posted a great infographic on unicorns. It leaves out one of my favorite unicorn facts, however: a group of unicorns is called a “blessing.”

There used to be actual unicorns in the world, but scientists call them elasmotheres.

On the Trail of King Arthur in South Wales

A recent post at the Celtic Myth Podshow highlights stories of King Arthur from Blaenau Gwent in South Wales.

The Arthur of medieval Welsh literature – be it in Welsh or in Latin – is the archetypal Celtic hero – a rough, vigorous, splendidly barbarian figure fighting boars and serpents, witches, dog-headed warriors and other dreaded enemies. He is often seen in conflict with the Church, and echoes the values and life-style of the Heroic society of the “Dark Ages”. We can forget the Round Table, damsels in distress, tournaments and the glittering Christian emperor until much later… The Latin Historia Brittionum (“History of the Britons”) – conventionally attributed to Nennius (1)– was originally composed c. 829/30 A.D. (2) and attached to it are a series of Mirabilia or “Wonders”: There is another wonder in the country called Ergyng. There is a tomb there by a spring, called Llygad Amr; the name of the man who is buried in the tomb is Amr. He was a son of the warrior Arthur, and he killed him there and buried him. Men come to measure the tomb, and it is sometimes six feet long, sometimes nine, sometimes twelve, sometimes fifteen. At whatever measure you measure it on one occasion, you never find it again of the same measure, and I have tried it myself. (3)

Several legends are then summarized. Very interesting!

Five Dwarfish Varieties from Around the World

Properly speaking, dwarves are a feature of Norse mythology. They are a tribe of subterranean smiths and craftsmen noted for their arcane knowledge and especially their skill in fashioning powerful magical items.

But these aren’t the only wise and secretive earth-spirits in world mythology, although they are probably the most frequently encountered in fantasy fiction. Here is a list of five fantastic beings that combine (in various proportions) affinities for (1) the underground world, including associations with mining, metals, and precious stones and (2) secret skills or knowledge—craftsmanship, magic, the healing arts, etc.—which they may or may not share with mortals.

Dvergar

Let’s proceed roughly from the north and west to the south and east. We begin, therefore, with the dwarves of Scandinavia and their cousins in other Germanic cultures. The dwarves of northern England’s Simonside Hills, for example, are of this sort. These dwarves formed the basis for J. R. R. Tolkien’s depiction of dwarves. In fact, the dwarves in The Hobbit all have names drawn from Norse mythology. They are also seen in characters such as Alberich the dwarf in the Middle High German Nibelungenlied. As already stated, these dwarves are renowned metalworkers and blacksmiths. In Norse mythology, they fashioned many of the magical items used by gods and heroes, including Thor’s magic hammer Mjölnir and the chain that bound the great wolf Fenrir. In some later legends, they are also accomplished healers. They can, however, be highly distrusting of outsiders. They also have a reputation for being greedy.

Dvergar are ill-tempered, greedy, miserly, and grudging. They are known to curse objects they are forced to make or that are stolen from them. They almost never willingly teach their magical knowledge. At the same time, they can be surprisingly friendly and loyal to those who treat them kindly. Contrary to popular misconceptions, dvergar are not particularly illustrious warriors—although their strength and overall hardiness suggest they would generally be able to hold their own in a fight.

Like trolls, Norse dwarves are sometimes depicted as turning to stone if exposed to direct sunlight.

Karliki

Karliki (singular, karlik) are fiendish dwarves from eastern Europe, inhabitants of the lowest recesses of the underground world. In Polish, the appropriate terms are krasnal, karzeł, or karzełek, although they are sometimes called Skarbnik, “the Treasurer.” These beings are very similar to dvergar, living in mines and guarding hoards of metals, gems, and crystals. Apparently they are even more prone to malicious behavior than their Nordic cousins. According to Slavic Christian folk beliefs, these beings are, in fact demonic. One source relates, “When Satan and all his hosts were expelled from heaven, says a popular legenda, some of the exiled spirits fell into the lowest recesses of the underground world, where they remain in the shape of Karliki or dwarfs” (see Ralston, The Songs of the Russian People, 106–107).

Karliki can be helpful toward miners, willing to lead them to rich veins of ore and protect them from danger. To those who offend them, however, they can be deadly, sending tunnels crashing down upon them or pushing them into dark chasms.

Dactyls

The daktyloi or dactyls are the dwarves of Greece and the Aegean. They are renowned smiths and healing magicians. In some legends, they taught metalworking, mathematics, and the alphabet to humans. The sisters of the dactyls are called hekaterides (singular, hekateris).

The daktyloi or dactyls are the dwarves of Greece and the Aegean. They are renowned smiths and healing magicians. In some legends, they taught metalworking, mathematics, and the alphabet to humans. The sisters of the dactyls are called hekaterides (singular, hekateris).

- Cretan dactyls are especially adept at healing magic, but they are also known for working in copper and iron.

- Idean (or Phrygian) dactyls may be the oldest tribe of dwarves in the Mediterranean region. They are rustic creatures from around Mount Ida in Phrygia and perhaps have their origin in earlier Hittite or Pelasgian earth-spirits. They claim to have invented the art of metalworking and even to have discovered iron.

- Kabeiroi are an offshoot of the Idean tribe that settled at Lemnos, Samothrace, and Thebes. They are divine craftsmen said to be descended from the god Hephaestus. They have an association with the sea and sailors that is quite unusual for dwarfkind. In some accounts, they are raucous wine-drinkers.

- Rhodian dactyls are dangerous underworld smiths and magicians sometimes called telkhines.

Khnumu

Dwarves have an esteemed place in Egyptian mythology. Mundane dwarfs or little people apparently suffered little or no prejudice in ancient Egypt. Some gods, most notably Bes, were depicted as dwarfs. These gods were originally protectors of households.

In addition to Bes, there were the khnumu (singular, khnum), subterranean earth-spirits who were helpers of the god Ptah, the creator of the world. Their name means “the modellers.” They are represented with muscular bodies, bent legs, long arms, large broad heads, and intelligent faces. Some wear long mustaches; others have bushy beards. By some accounts, they have the power to reconstruct the decaying bodies of the dead. Other accounts say they were the ones who first taught humans the magical arts.

In later times, khnumu might be called pataikoi (singular, pataikos), “little Ptahs” in Greek. Phoenicians carved images of pataikoi on the prows of their ships. The Greek historian Herodotus compared them to the seafaring kabeiroi.

A similar figure occurs on early Babylonian seal cylinders, where it is given the Sumerian name “the god Nugidda” or “the dwarf.” This figure is sometimes depicted dancing before the goddess Ishtar. It is a matter of speculation whether this Mesopotamian dwarf-figure was the inspiration for the Egyptians and Phoenicians or whether it was the other way around.

Yakshas

Yakshas hail from India. They are found in Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist literature. They are a broad class of nature-spirits and caretakers of treasures hidden in the earth and in tree-roots. Their king is Kubera, the god of wealth and protector of the world. He is often depicted as a fat man holding a money-bag and adorned with jewels.

Yakshas function as stewards of the earth and of the wealth buried beneath it. Depending on the story, yakshas may be either benign nature-spirits associated with woods and mountains or foreboding monsters that ambush travelers.

Male yakshas are portrayed either as warriors or as stout, dwarf-like beings. Female yakshas, called yakshis or yakshinis, are often depicted as young, beautiful, and voluptuous.

Like the Egyptian dwarf-god Bes, yakshas are often protector figures. In Thai Buddhism, yakshas often feature in architecture as guardians of temples. These fearsome yakshas are depicted as green-skinned with bulging eyes and fangs. In Thai folklore, yakshas often figure alongside ogres and giants.

In Jainism, yakshas are often propitiated to bring fertility, health, and prosperity.

Satyrs: Greek Spirits of the Wild

Satyrs are associated with forests and mountains in both Greek and Roman mythology. Hesiod (7th cent. BC) considered them the “brothers” of the mountain nymphs and Kouretes. Whatever their genealogy, they are uninhibited children of nature: earthy, reckless, seductive—and dangerous if threatened. They are the quintessential “bad boys” of the faery world, brazenly flouting the norms of civilized society. In keeping with their untamed nature, their traditional garment is a panther pelt.

Despite their wildness, satyrs do have an appreciation for at least some of the gifts of human culture. They love music and dance, for example. In fact, they have a special form of grotesque, vulgar dance called the sikinnis. They are also associated both with Pan, the Greek god of the wild, and Dionysus, the god of wine. They are notably hardy and resistant to fatigue, able to dance for hours on end, for example, or remain (relatively) sober no matter how much alcohol they consume. They are lovers of wine, women, and revels. They have a particular infatuation with nymphs.

There are two common depictions of satyrs in Greco-Roman art. Young satyrs are called satyrisci (singular, satyriscus). They are graceful beings with elfin features and pointed ears. Praxilites’s sculpture “Resting Satyr” depicts a satyriscus.

The earlier depiction of satyrs made them older, more animalistic, but also more powerful. These satyrs are classified as sileni (singular, silenus). Sileni are bearded and strongly built. They have the ears of a horse, a horse-like tail, and sometimes even the hooves (or the entire lower body) of a horse. Sileni are the oldest, wisest, and most magically adept of satyrs.

It should be noted, then, that satyrs are not to be confused with fauns or “goat-men.” As time progressed, Greek satyrs became blended with Roman fauns in the telling of the myths. The two, however, were originally different sorts of beings. Satyrs are, in fact, fully humanoid (at least in their youth). Medieval bestiaries often compared satyrs not to goats but to apes or monkeys.

World-building: Extensive, Minimal, Top-down, and Bottom-up

Philip Overby has a new post up at Mythic Scribes about that perennial topic among fantasy writers, world-building. Philip lays out the pros and cons of both “extensive” and “minimal” approachs to world building, and he does it quite well. I’ll go ahead and state my preference for extensive world-building—as long as it doesn’t bog down the story.

I commented:

I think of it sort of like a flower garden. People who come by to admire your roses and petunias don’t really care what sort of fertilizer you use or how you decide when to plant or the brand of your favorite set of clippers. They care about the finished product, not the process. And yet, when the other members of the local gardening society come around, they love to talk shop, share tips, etc.

I’m not sure what proportion of fantasy readers are like the members of the gardening society and want to delve deeply into the appendices in the back of the book (or the Wiki or whatever). I am fairly confident, however, that that number is greater than zero. 🙂

In addition to “extensive” and “minimal,” I find it helpful to think in terms of either “top-down” or “bottom-up” world-building. Top-down world-building gives you the big picture of what is actually possible in this new, fantastical world—and why, given this broad context, things actually happen the way they do.

I’m thinking here of the basic mechanics of the world, the elements that inform the overall direction of the story. Top-down world-building looks at the sorts of broad subject matter one could study about our own world: history, technology, geography, religion, politics, etc. Add to this the things that would be a part of a well-rounded education in our world if, in fact, our world was a fantasy setting: How does magic work? What sapient species (elves, dwarves, fauns, talking animals, etc.) exist, and how do they all get along?

It’s a good idea for writers to have a pretty firm handle on these sorts of issues. Philip is right that at least some of this work really should be done before writing commences. I would urge, however, that writers spare us the info dump. If the world is engaging enough, I’ll certainly ask for more “behind the scenes” information. But I don’t want all this fascinating detail to get in the way of a great story. Rather, let these kinds of issues bubble up organically from within the story itself.

Bottom-up world-building is different. These are the elements that lend a certain tone or “color” to the narrative. They may very well be the sorts of things writers dream up on the spot to give their world a greater sense of verisimilitude or simply to entertain the readers.

One good example of what I mean by bottom-up world-building is the in-universe terminology characters use to talk about the various features of their world. What sort of slang, shorthand, technical terminology, or even profanity grows naturally out of the way your world is put together? You can develop an entire magical system using generic terms like “non-magical person,” but doesn’t it add something to the story’s texture to call such a person a “Muggle” (if you’re Harry Potter) or a “straight” (if you’re Harry Dresden)? For me, bottom-up world-building usually begins when I say, “I need a term used by group X to refer to concept Y” or “I need a weird or magical way people in my world would perform ordinary activity Z.”

I’ll be honest and admit that some of my bottom-up world-building takes the form of puns and gags. My purpose is to entertain, after all. So maybe my protagonist is listening to a country-western song in which the cowboy-wizard’s three-headed dog runs away. Or maybe my elves fire “elf-shot” from a twelve-gauge rather than a bow and arrow. (I actually decided to include that last one in Children of Pride fairly late in the writing process. Fortunately, I already had enough of the magic system worked out to explain [to myself!] how it could work. Maybe someone will explain it to my protagonist in a later volume…)

Top-down and bottom-up complement each other. In fact, the two can even build upon each other as the writer reflects on how his or her world is taking shape.